|

|

04/26/2017 |

These past few weeks have been totally crazy. In the front of our shop, we're busy building three workbenches and their accoutrements for Handworks in Amana next month. In the back of the shop we're busy making saws and other stock for the show. This coming Saturday is the massive Festool Roadshow (free food, drink, gift bags, etc. - check it out) and that requires tons of legwork too. We also started a new blog of videos we found on various woodworking topics that we think others might find interesting too.

While all of this is happening, I was seriously concerned I would miss the "Small Wonders" show at the Cloisters.

Some background:

I have been going to the Metropolitan Museum since my youth – I grew up a few blocks away in a small tenement that is now the parking garage for a fancy building. I’m also a big fan of The Cloisters, the Met’s affiliated museum near the northern tip of Manhattan. The Cloisters is made up of cloisters excavated from French monasteries, indoor chapels and contemplation gardens filled with plantings of fruit trees and medicinal herbs that would have been used in medieval Europe. I like to visit the Cloisters every year or so and take in the ambiance of the gorgeous architecture, tapestries and other art.

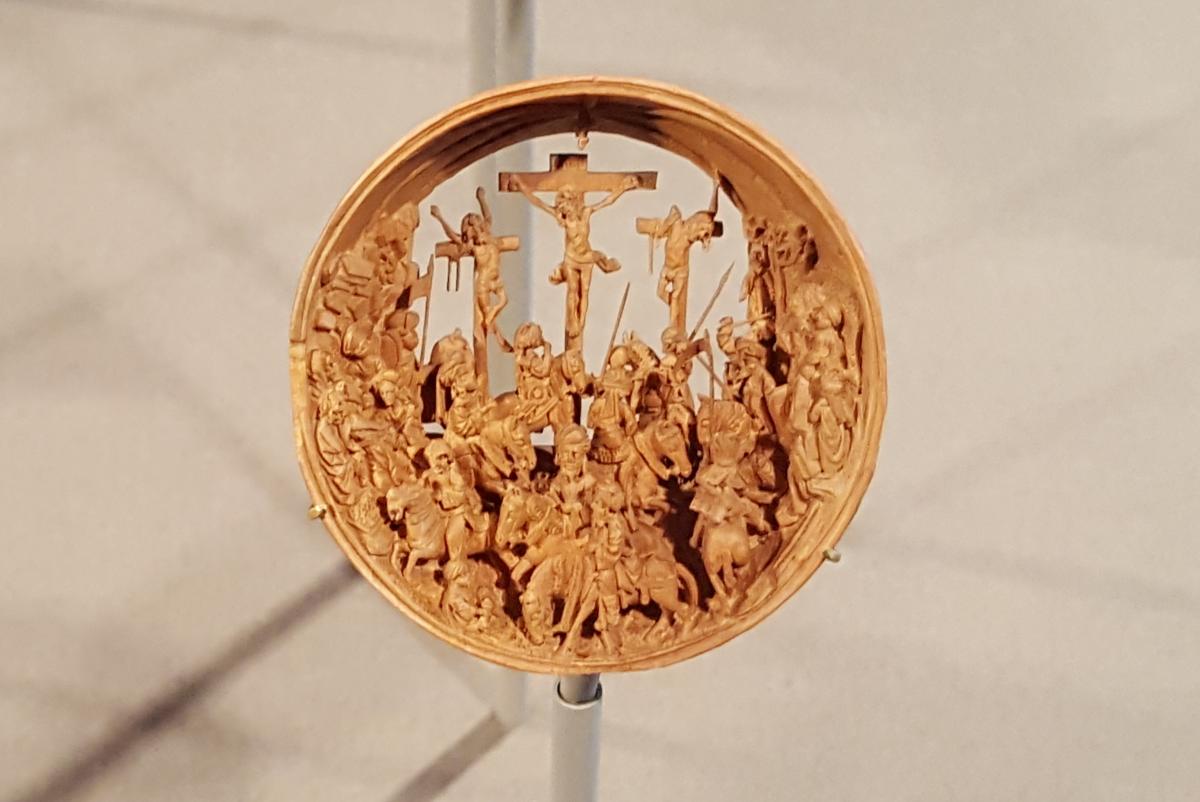

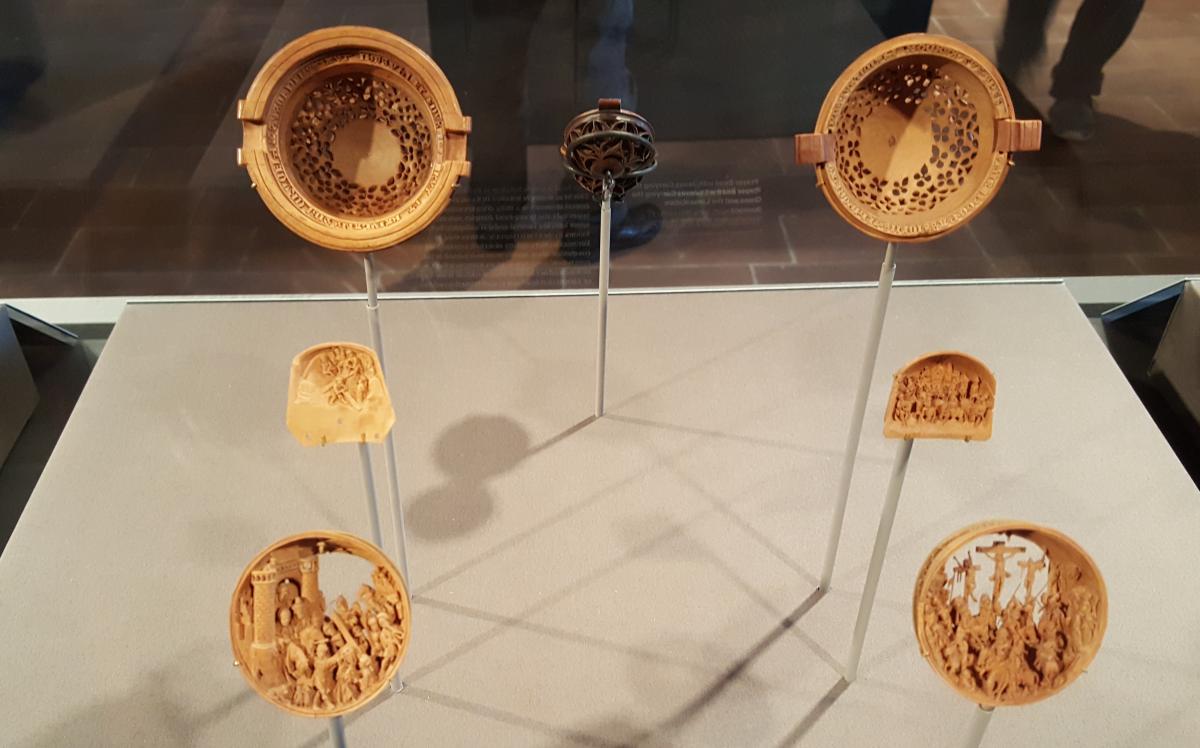

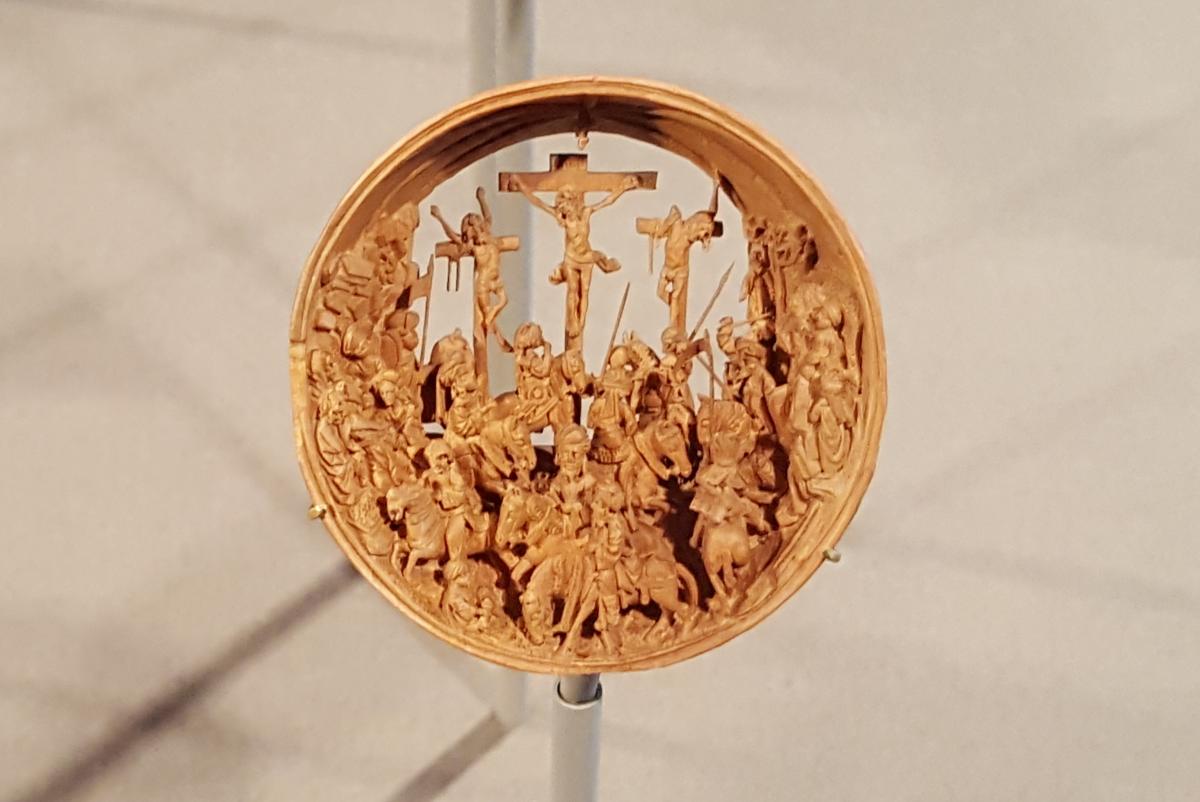

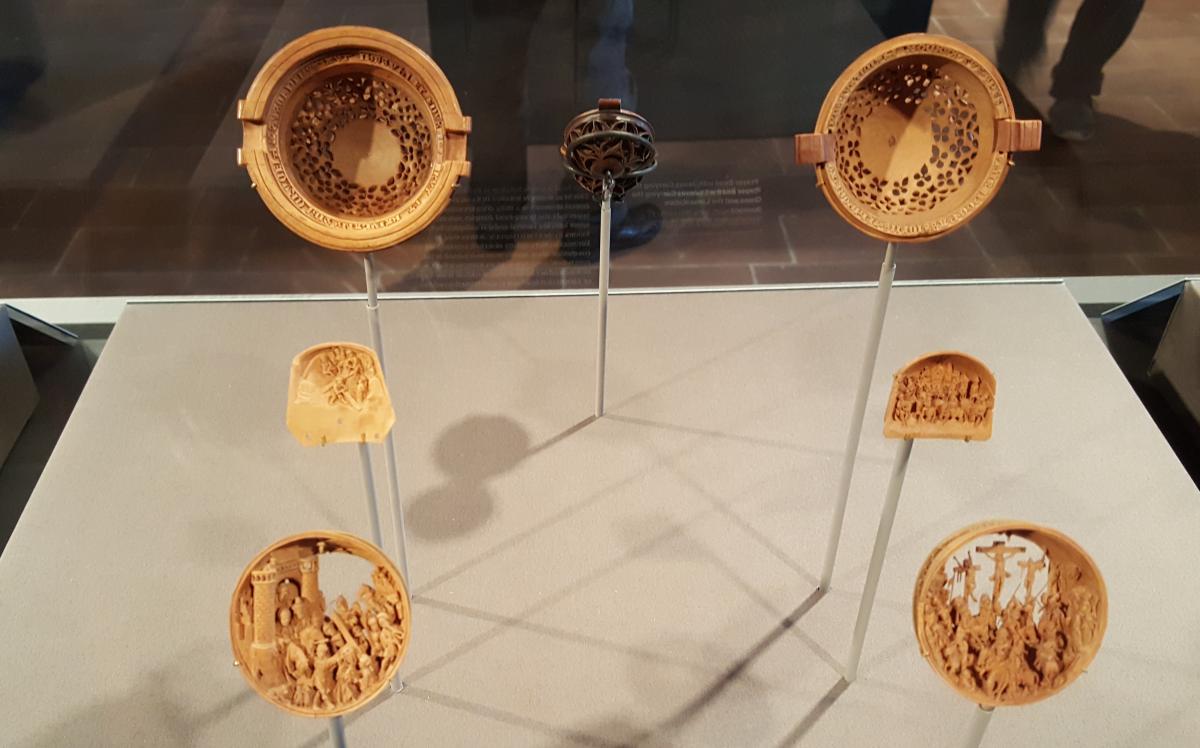

The first and still favorite book of carving I ever owned (when I was about 8) Whittling and Woodcarving by E. J. Tangerman, which had a picture of a miniature boxwood carving from the late 15th/early 16th century from the Met's collection. It's about 2" in diameter. When I visited the Met regularly as a kid, I made it a point to search out the carving. As an adult I would regularly stop by to see it at and I'd always be filled with wonder. So I was determined to catch the show about these boxwood carvings,"Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures." The show is a joint project organized by the Met, Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and will be held in all three museums (and maybe others). The micro-carvings include prayer beads, altarpieces, coffins, skulls and other tiny creations. They are shockingly intricate and shockingly tiny. Some open up to reveal intricate tableaux. The next time I see a walnut shell, I’ll be disappointed if I don’t see an elaborate carved crucifixion within.

The carvings were both popular and mysterious in their own time. Henry VIII was a fan, as were many other rich and royal collectors. But the artists, and their techniques, were largely unknown. As a Dutch collector in the 17th century complained, “It is regrettable that the maker of this ingenious piece has not made himself known with any sign.” More recently, conservators and historians used CT scans and other scientific tests to analyze over 100 of the micro-carvings, and learned some interesting things about the carvers’ techniques. The most complex carvings were made in layers, with a given layer containing different figures of the tableau. The layers were then installed with tiny pegs and glued, but made to seem as if everything were carved from a single block of wood. If the carver needed access to a hard-to-reach area, he incorporated slits through which he could pole a tool through, then artfully concealed the slit in the artwork. Conservators discovered less careful, even somewhat shoddy work such as multiple holes, in some of the carvings’ undersides.. But peeking behind the curtain is possible only to those who dismantle the carvings, leaving the rest of us to marvel at the illusion of perfection.

According to a New York Times article about the exhibit, “The original woodcarvers used foot-powered lathes, magnifying glasses made of quartz, and miniature chisels, hooks, saws and drills. The works were so detailed that individual feathers are visible on angel wings, and dragon skins are textured with thick scales. Crumbling shacks are shown with shingles missing from their gabled roofs. Crenelated spires have scalloped molding tucked along their doorways, and there are deep grout lines between bricks. Saints’ robes and soldiers’ uniforms are trimmed with buttons and embroidery, and there are nearly microscopic representations of jewelry and rosary beads.”

For me, aside from my longstanding interest in one of the beads - in fact the the very one that the curators disassembled for the show - the amazing realism of the miniatures is one of the most exciting aspects of the carvings. There are also many other thrilling aspects. They have remarkable grace and fluidity. And although everything is off limits to grubby hands, some of the components within the dioramas, such as doves displayed in birdcages, can move around.

This coming Sunday (the day after the Festool Roadshow) I am going back to the Cloisters to hear a talk on these carvings by David Esterly, a scholar and master carver. I am looking forward to his insights on these miniatures. In part two of this blog I expect to have something interesting to report back.

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

Good luck at Handworks and the Festool show!